The weather story behind inversions

By MWIS forecaster Garry Nicholson:

The past couple of days have brought some stunning scenes thanks to inversion conditions placing the mountain tops above banks of low level cloud or fog. It's a magical sight to be on high above an ocean of fog with just your neighbouring mountain islands for company.

This was the scene from above and below the fog bank around Glencoe this morning.

Many of you have been asking how these situations occur, and how to watch out for them happening so you can plan to be up there when they do!

It must be said, that forecasting the height of cloud tops can be one of the trickier aspects of mountain forecasting. Those tantalising moments when you reach a summit, can almost see the sun above you, but you're still just in the fog. Oh so frustrating... sometimes all you need is a taller trig point to stand on!

The past few days have been somewhat more straightforward, in that the inversion layer was due to be low enough to confidently produce fog in or above the glens, valleys and coasts, leaving most higher mountains in the clear.

So what has been happening over the past few days, and what are the vital ingredients for the avid inversion bagger?

Stability

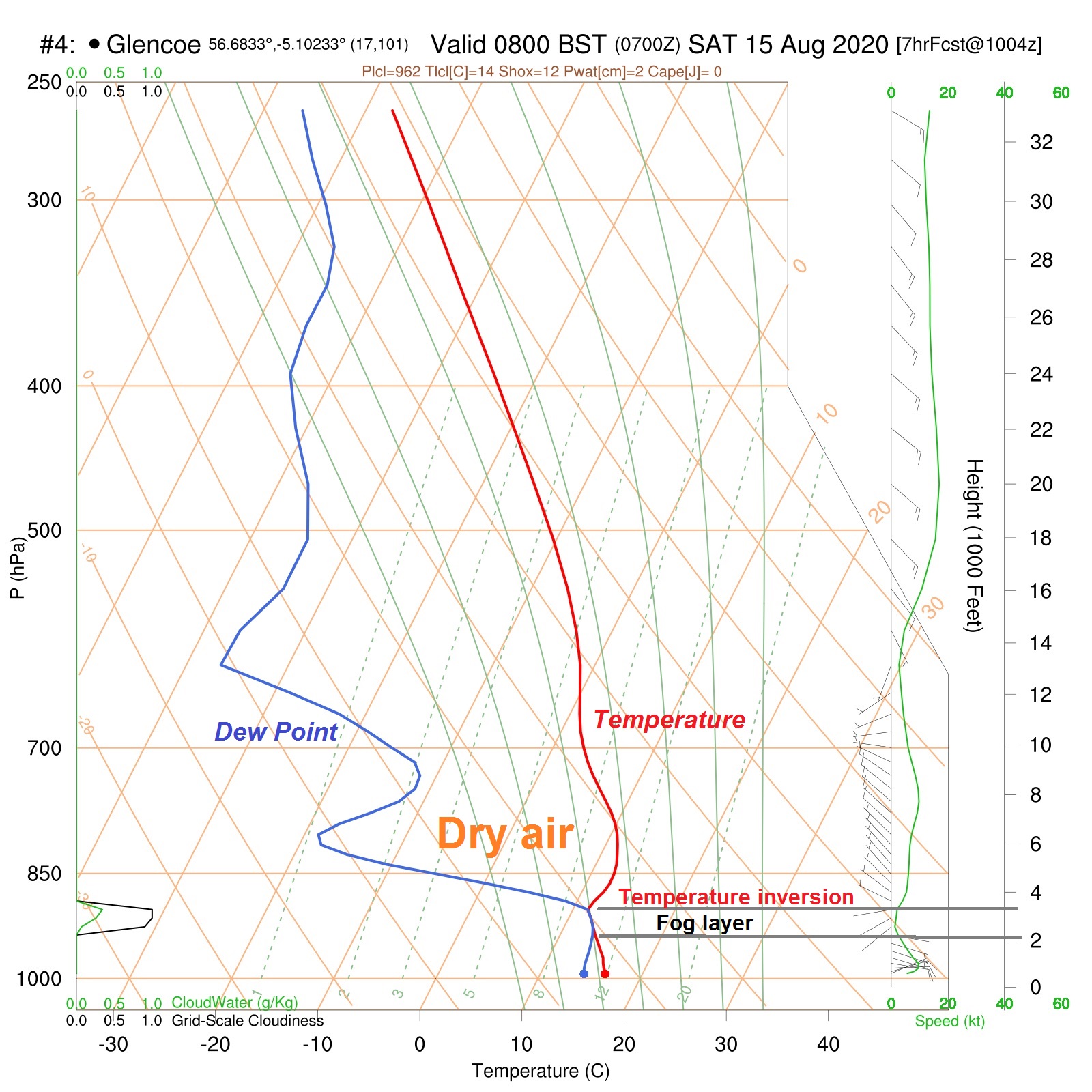

This is a vertical profile of the atmosphere, from Saturday morning at Glencoe, showing the change of temperature and dew point with height.

When the dew point and temperature lines meet, the air is saturated, and fog or cloud is present.

Above this, we have dry air with a low humidity percentage, because the dew point value is a long way below the temperature.

More commonly, temperature falls steadily with increasing height, but here the temperature value is slightly higher in the zone just above the fog. This is what we mean by an 'inversion' - it is a reversal of the usual situation of cooling with height.

This is a 'stable' atmosphere, where air is gently descending, and warming through compression.

By contrast, an unstable situation would see a more rapid fall of temperature with height - which was one of the factors behind the thunderstorms earlier in the week (although excess low-level heat and humidity were also key on this occasion).

High pressure and moisture

This is the current pressure chart. Notice high pressure located to the north of Scotland.

When high pressure exists, this sets in motion the gentle descent of air mentioned above. If the descent occurs for a few days, it often reaches the level to interact with our highest mountain tops, placing them above an inversion.

Where there is sufficient moisture present in the lower layers of the atmosphere, this can become trapped beneath the inversion, whilst the air above dries out as it warms. The very humid air which came up from the south earlier in the week has now bumped into cooler air at low levels coming around from the northeast over the North Sea and north of Scotland.

This combination thoroughly saturated the air and formed the extensive blanket of cloud seen on the satellite image below. It has made this a particularly good summertime inversion!

Notice how our inversion fog / low cloud layer is very smooth topped, highlighting its stable, laminar properties, compared to the much clumpier appearance of the unstable rain bearing clouds over southern Britain and Ireland, where thunderstorms are still around.

The slow-moving weather patterns we're seeing at the moment are ideal for an inversion, because the air doesn't get moved on or mixed up too easily, and the existing amounts of moisture are more or less maintained.

Air with high low-level moisture loadings usually originate from the south at all times of year, especially if they have travelled toward Britain over the sea for some time. Northerly sources are less moist, and don't saturate as easily, but can help to saturate pre-existing humid air such as at present.

A gentle amount of wind is useful, just to keep supplying enough moisture. The onshore easterly component is certainly keeping eastern regions covered in the North Sea murk, whilst out west, the early morning fog caused by overnight cooling is soon lost over inland areas once the daytime sun evaporates the residual moisture.

Valley fog can become banks of low cloud if the lower air warms slightly, and gentle uplift carries the fog onto middle slopes. In some situations, this thins out the fog layer so much that it disperses completely.

If a frontal system comes through, it would force a change of air mass, and the delicate balance of temperature and moisture currently in existence would be lost. Changes in airflow direction, wind strength, or the overall pressure pattern will all spoil the inversion environment, either by dispersing the cloud or by lifting it into higher layers which then sit on or above the mountains.

We then just have to wait for the next time the weather situation gets back into inversion mode!

Quick perfect inversion recipe:

High pressure nearby - almost stationary for a few days

Slow-moving weather patterns

Plenty of low-level moisture - after rain, or due to air mass characteristics

Air with a history of coming from the south and/or over the sea for a long time

Not too much wind

Absence of fronts

Check out our social feeds for some of the excellent pictures you've taken - don't forget to tag us in your pics and we'll share them to the MWIS world!