By MWIS Forecaster Garry Nicholson:

We've had the first proper northerly outbreak of this winter season this week, which brought lowering freezing levels and some snow to higher mountains of Britain.

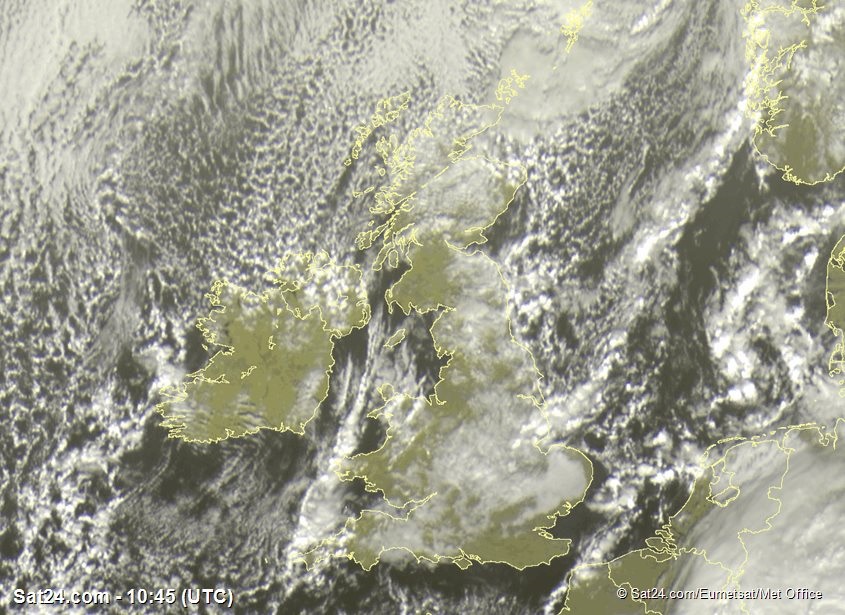

The satellite image from Wednesday was a classic scene for this type of weather pattern during the 'winter half' of the year.

The speckled clouds streaming in from the north are small convective cells, triggered by a cold air mass from Arctic origins moving southward over a comparatively warmer sea. This makes the air unstable, with thermals rising to form shower clouds. These often form into the honeycomb-like pattern we see on this image.

Any air coming from a cold source during the winter will exhibit this tendency. Sometimes a 'cold' westerly flow which has originated from Greenland can drive these showery cells into Britain from the west, rattling in as heavy showers to our western mountains.

The northerly airflow is then modified as it interacts with our coastlines, being funneled through caps, chiefly the North Channel between Scotland and Northern Ireland. This funneling effect causes convergence of the air, which forces it to rise, further aiding the process of shower formation.

The result is a distinct band which is then carried away southwards on the northerly wind over the Irish Sea. This often tracks across the far west of Wales and is comically referred to as a 'Pembroke Dangler'. The same feature also runs south into Cornwall. Locally, shower after shower will occur, but a few miles away sees very little precipitation. On the synoptic map below, it is shown by the 'twig-like' line which indicates a convergence zone. This is slightly different from the solid black lines which are 'troughs' - those create clusters of showers caused by slight temperature and wind changes higher above the surface.

During the extended winter period, land-based convection becomes almost non-existent, as the weak sun doesn't heat the land enough to trigger rising thermals, so many inland areas are often free of showers, especially if sheltered from the onshore winds.

Contrast this with springtime, when the main trigger for 'April showers' is a warming land, and showers then bubble up over the land during the daytime. You can also get the 'winter-type' of showers too in spring, usually in the mornings, coming in from the coasts for a few hours.

In high summer, the relatively cool sea compared to the air temperatures will inhibit shower formation over the water, meaning the sea areas are generally clear, whilst showers and thunderstorms are triggered by land-based heating and daytime thermals.

It's these subtle interactions which make our weather so varied from season to season!