Unstable air and heavy wintry showers

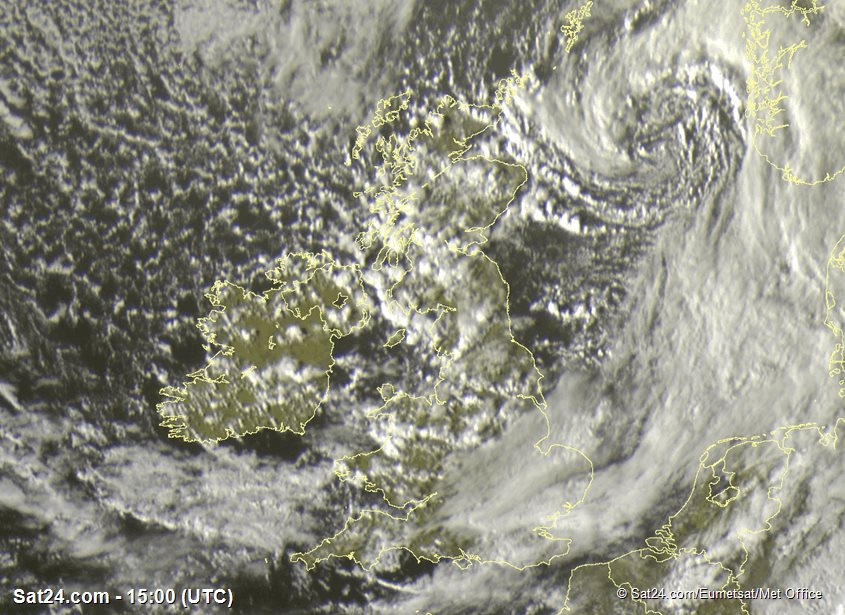

If you've been out on the hills this past day or so, you may well have been caught in some hefty bursts of rain, hail, or snow on the higher tops. It's been a classically showery weather regime, all triggered by the temperature of the air above our heads. Friday's satellite image (below) highlights the extent of shower clouds across Britain. A centre of low pressure was located over the North Sea. A polar maritime air mass was affecting the country on west to northwesterly winds.

We have seen a trough of colder air aloft move in across the British Isles. In forecasting, we often look at the 500mb pressure level, which exists around 5km above the surface - (as you go higher in the atmosphere, there is simply less air above you, so pressure becomes lower).

The temperature we find at 500mb gives a good clue about the stability of the air mass. Lower temperatures higher up result in a more rapid fall of temperature with height, something we refer to as the 'lapse rate'. When this real world fall is greater than would occur in an idealised state in physics, we call it 'unstable'. A greater lapse rate means greater instability and heavier showers!

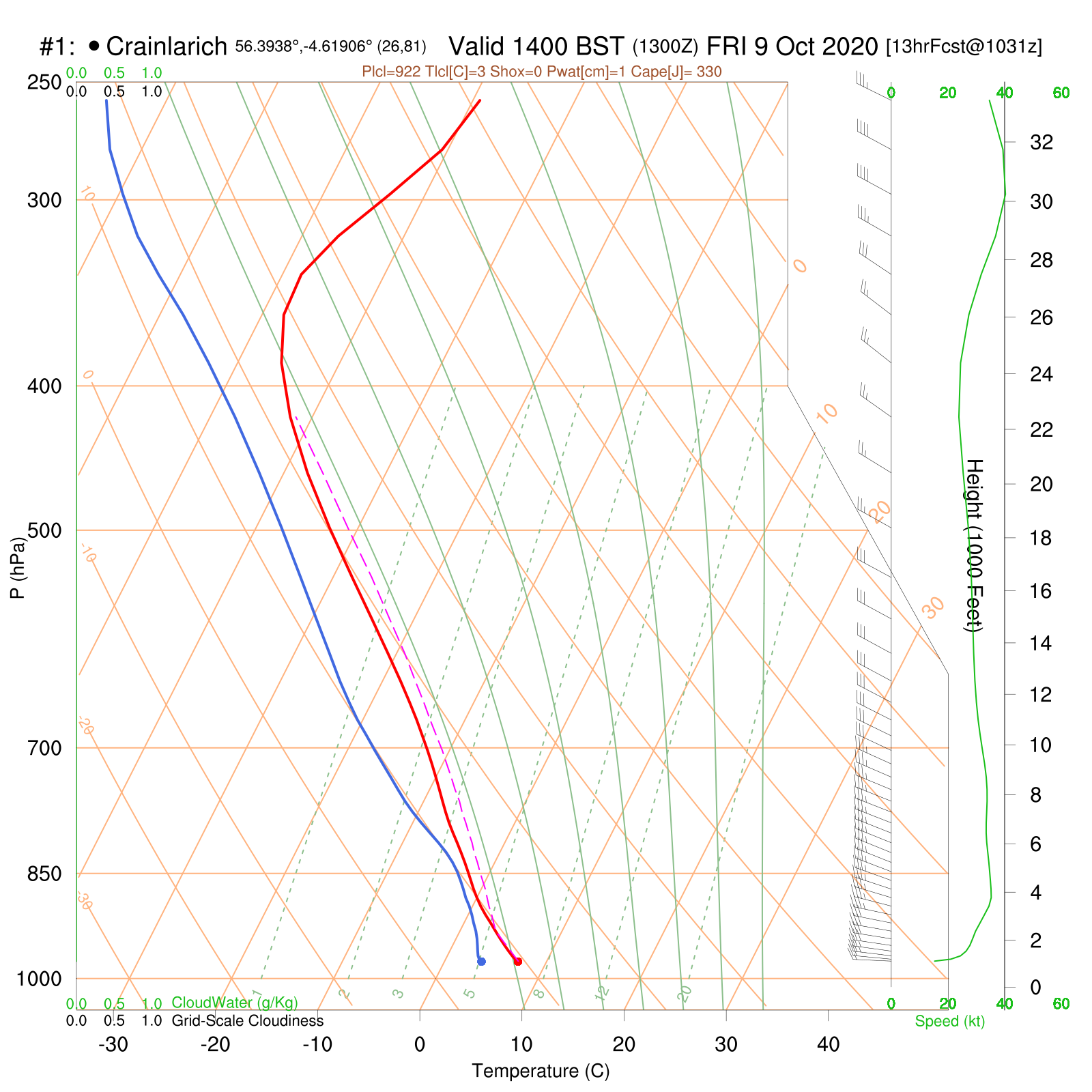

This means air can rise buoyantly, because any rising 'bubble' of air is always warmer and therefore less dense than it's surroundings. As condensation occurs, clouds form - the fluffy frothing variety which bring showers. On Friday, the temperature at 500mb over Scotland was as low as -33C (shown below), perfectly normal, but the required ingredient for instability and showery weather. In winter, values of -40C can occur at this level. In more stable atmospheric situations, values of are nearer a balmy -15C.

The vertical profile of the air shows this instability, which on Friday was up to around 400mb, around 24,000ft as shown. The red line on the chart below is the temperature value with height. The pink dashed line is the theoretical value indicating the instability of this profile. (Remember recent blogs when we were dealing with inversions, the temperature line had a 'nose' lower down, and didn't then fall as rapidly with height.)

This is a good example of 'cool weather' convection, bringing showers, with hail and isolated thunder possible. Summertime instability and thunderstorms also require cooler air aloft, but are aided by increased heat and humidity in the lower levels which set off the rising thermals.

Many of you may be familiar with the '528 line' in forecasting snow. This is a thickness line, referring to the depth of the layer of atmosphere up to 500mb. '528' is a value in decameters - add an extra zero for meters. So, 5280m above the surface. The lower the 'thickness', the colder the air mass. Colder air is more dense than warm air so it occupies less space. This value is simply used as a rule of thumb in forecasting snow to low levels. In that situation, cold air is near enough to the surface to allow precipitation to fall to low levels as snow, without melting into rain. Friday's thickness was around '536', so not quite enough to bring snow all the way down to sea level, but it was enough to bring it down sometimes below 700-800m across Scottish mountains as was seen.

As we move into the winter season, these episodes of cold air aloft form a regular part of our mountain forecasting. They're fairly straightforward in terms of a general weather story - it usually involves the full kitchen sink being thrown at you... Snow, hail, squally winds, thunder, suddenly appalling visibility, whiteout... You know the type of day we mean!

Stay up to date with our forecasts as the seasons change. Here's to some 'good' winter weather in the months ahead!