Managing Thunderstorm risk in the mountains

Photo credit: Akbar Nemati/Unsplash.

The risk of being killed by lightning in the UK mountains is small but real and needs to be taken seriously. Nobody wants to be caught up a mountain in the middle of an intense thunderstorm. On some days, it’s best not to go out. There are many days in summer when ‘isolated chance of thunderstorms’ are forecast and that might be within your own personal risk tolerance, especially if you can add a few mitigations into your day.

This blog will explore ways to make better decisions about managing this risk and give you ideas of things you can monitor while out to decide whether to carry on or cut your day short.

Identifying risk

Mountain weather forecasts should be a standard part of your planning a day in the mountains. The Mountain Weather Information Service will alert you to the possibility of thunderstorms, including when and regions they might happen. Unfortunately, the exact location of showers/thunderstorms is impossible to predict.

In summer, generally speaking, thunderstorms are most likely in the afternoon on hot days. Days having a ‘muggy’ feel early on are a particular risk. If there were thunderstorms the previous day that is another big warning sign to be extra vigilant. Thunderstorms most often happen inland away from coastal areas but this is not always the case. Again, the forecast will hopefully help with identifying this.

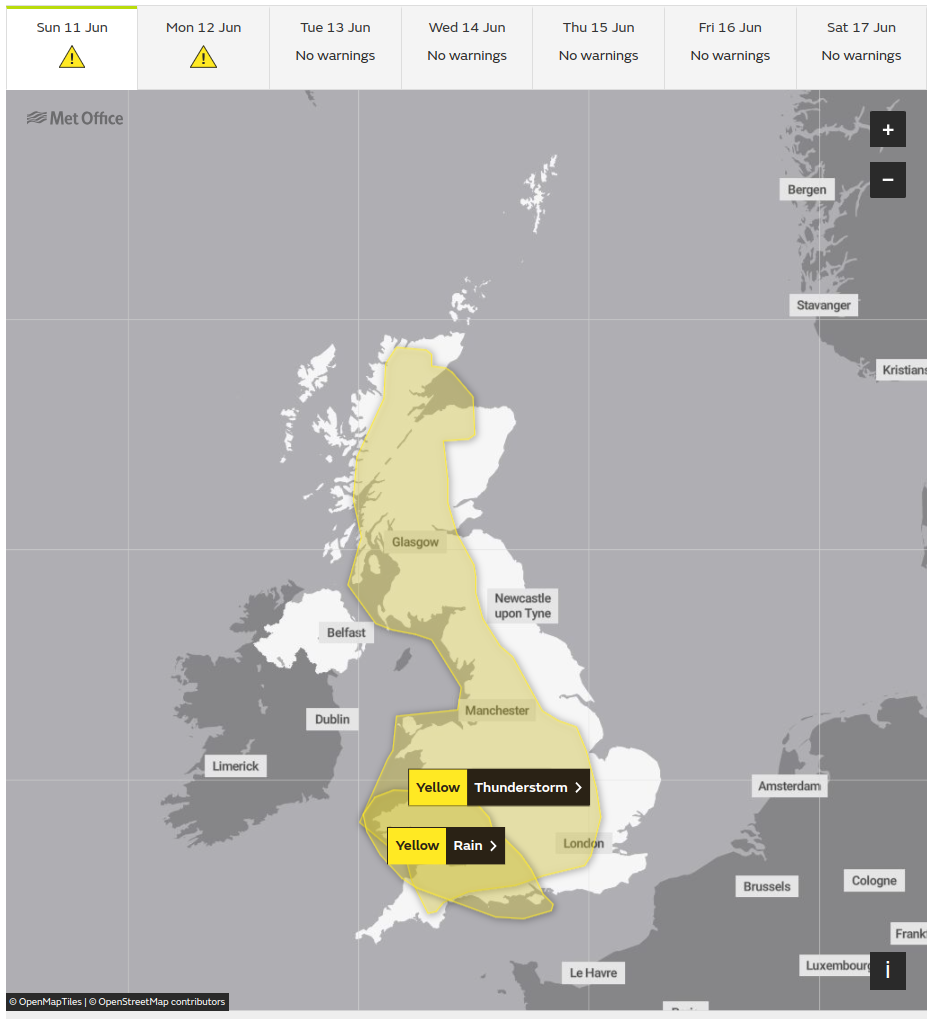

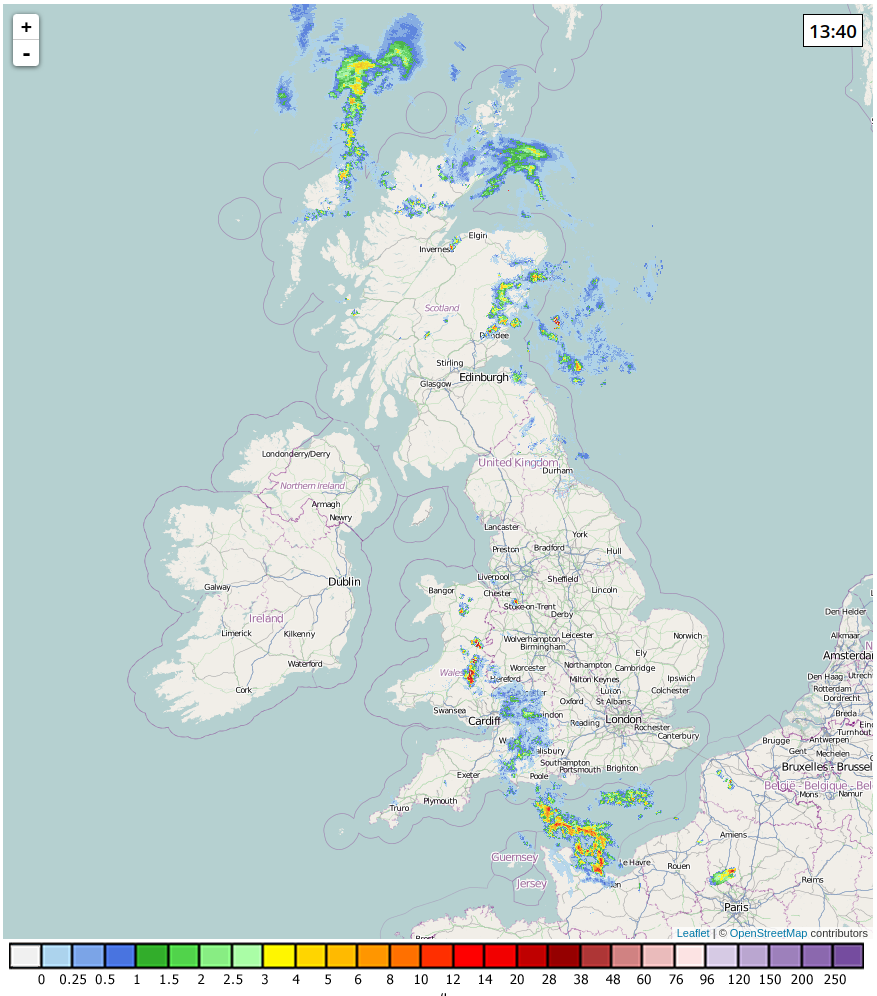

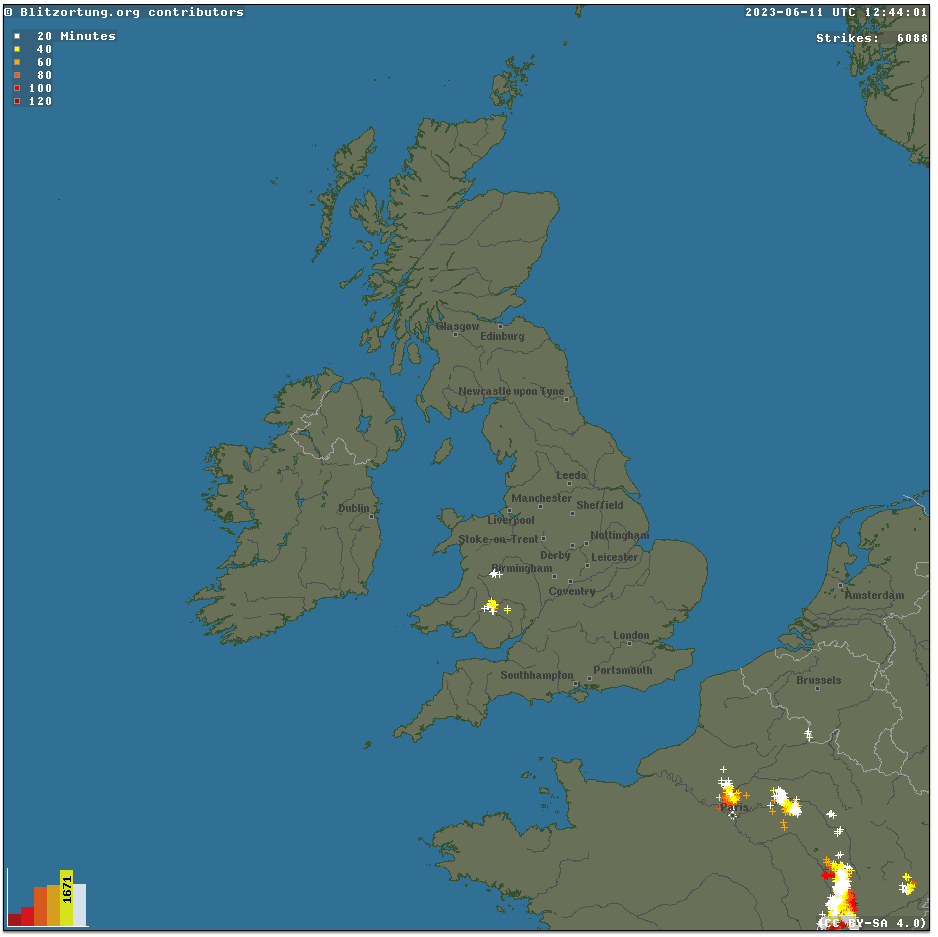

On the morning of your trip, checking the current weather observations is very helpful. If there are heavy showers in the morning this is likely to be an alarm bell for later in the day. If there are already lightning strikes, even if it’s 50 miles or more from your planned destination, this is another major warning sign. Checking the latest rain radar and lightning detector websites is a good way to get this information. It’s also worth checking the Met Office weather warnings; they will put out a warning if thunderstorms are likely to have an impact on the mass population.

On the MWIS forecasts the language we use gives an indication of how likely a storm is. Look out for these words showing increasing levels of risk: ‘isolated chance’, ‘localised’, ‘chance of’, ‘likely’, ‘clustering’.

Netweather.tv's rain radar showing an active heavy shower over Wales and a scattering of showers in the eastern Cairngorms on 11 June 2023.

Blitzortung.org's lightning detectors showing recently lightning over Wales and France. This is the same storm picked up by the rain radar in the previous image.

The Met Office Weather Warnings showing a Yellow Warning for Thunderstorms over a large part of the UK on 11 June 2023.

Managing risk

There are a number of strategies on how to manage thunderstorm risk. You will likely use a combination of techniques and different parties may choose different approaches based on their skill, fitness, risk tolerance and, perhaps, inexperience.

By far the safest way to not get hit by lightning is to not go out on a day when thunderstorms are forecast. This will be the preferred option for many people.

The next level of risk is to go with modifications built into your plan for the day:

Can you climb a lower mountain?

Can you do a shorter day out?

Can you choose a region with less risk, possibly more coastal, than you initially had planned? The forecast should help you identify these areas.

Can you have a very early start? It’s not unusual for me to have an Alpine start and be walking by 5 am on days when there is a high risk of afternoon storms.

Can you plan escape routes into your day? If conditions are looking bad, you can cut your walk short using pre-planned descent options. A day with thunderstorms forecast is not a good day for the Five Sisters of Kintail or the Aonach Eagach for example as there aren’t many escape options.

Cumulus forms, whatever their form, early in the morning is a warning sign of heavy showers and/or thunderstorms later.

Image credit: Hans Isaacson/Unsplash

Your fitness and ability to move quickly in descent will also come into your decision making. A fell runner may well be more willing to go high on a day with thunderstorms, knowing it won’t take them long to descend. Someone who knows they are very slow on descent may need to make more conservative choices about their route or their willingness to turn around when they see early signs.

Ongoing monitoring

If you do decide to go out, stay active with your monitoring of conditions through the day.

Using the Scottish Avalanche Information Service's Be Avalanche Aware, sometimes referred to as Be Adventure Aware, framework can help you make better decisions. You will be less influenced by natural human biases of wanting to press on and ‘it won’t happen to me’. During your planning, journey and key places (escape route junctions) consider: the current and developing conditions; you and your party's fitness, experience and motivation/biases; and the terrain you’ll be crossing, how exposed or escapable is it? This post isn’t the place to go into this framework in detail, but spending time understanding this model will help you make better decisions about everything from avalanche and thunderstorm avoidance to committing to a hard mountain bike descent or trad climbing lead.

As you monitor the conditions look out for, in order of increasing seriousness:

Cumulus clouds that become taller than they are wide are a warning of an impending storm. The dark underneath of the cloud and the 'moody' sky behind are both warning signs too.

Image credit: Ivan Ulamec/Unsplash

Cumulus clouds early in the morning. Even if they are small they are a warning sign of ‘instability’ and the fact that they may turn into Cumulonimbus thunder clouds later in the day. On most summer days you won’t see Cumulus clouds until late morning or midday.

On-off blustery conditions during an otherwise calm day. This is a sign that thermals are taking off which will cause clouds to develop. The sooner in the day this happens the more likely storms will be later.

Cumulus clouds starting to become taller than they are wide. This shows vertical development and the more that carries on, the more likely thunderstorms will be.

Beginning to see heavy showers around you on other hills

Seeing increasing showers or lightning on the live observation web pages. If you have a good phone signal, it’s probably worth checking every now and then. This will give you an idea of nearby conditions outside your line of sight or ability to hear.

Hearing thunder or seeing lightning. You will have heard that the time between a flash of lightning and hearing the rumble of thunder gives an approximate distance to the storm, every three seconds equates to 1 km, but remember this will take vertical distance into account as well as horizontal. Lightning can strike a long way from the actual storm, so physical distance is no guarantee of safety. If you start seeing lightning and hearing thunder it is definitely time to use your pre-planned escape route and start heading down.

The sky suddenly going very dark. This is a sign that you are under a very big cloud, at least a few kilometres tall; the height of the cloud is not letting light through. This is likely to produce very heavy showers and possibly lightning imminently. Take immediate action.

Heavy rain and/or very short delays between lightning and thunder. Take immediate action.

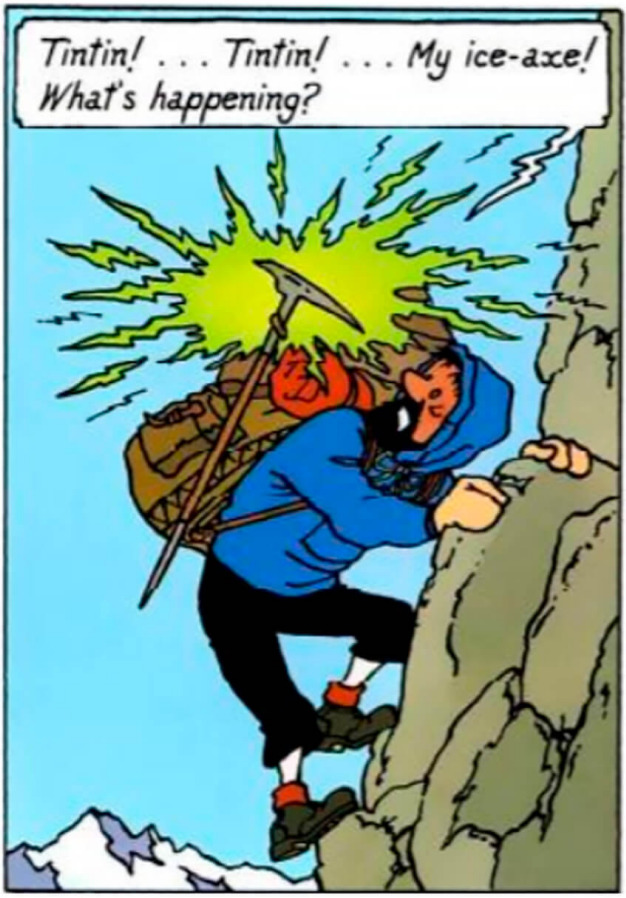

Metal objects buzzing, humming or beginning to glow. ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ is an indication of electrical charge building in your vicinity and a strike being very likely. Put metal objects down and get away from them. Take immediate action.

What to do if caught

With careful planning, observation and a willingness to turn around hopefully you won’t need these tips. I have never had to use them in anger.

If you reach situations 7 or above try to do the following:

Start losing height as quickly as you can even if this means you may need to reascend later to get safely off the hill. Consider jogging or running if you are physically up to it. Do not get yourself onto serious steep ground when doing this as this will have its own set of risks which may outweigh the lightning risk.

Get away from tall objects such as trees or foots of cliffs. Do not use these for shelter.

Avoid sitting in caves or under boulders. Sparks can cross these gaps and will go through you.

Spread out from other group members, aim to be 20 m apart to minimise the impact of a strike

Sit on your rucksack in a squat position to insulate yourself from the ground. The electrical current from a nearby strike will flow along the ground.

If the worst does happen call Mountain Rescue (999, then ask for the Police and then Mountain Rescue) and start appropriate first aid.

Tin Tin's climbing partner gets worried by St Elmo's Fire in this comic from 1962.

Image credit: Hergé 1962

Closing thoughts

Lightning strikes may seem unlikely in the UK but they do happen. A woman was killed in Glencoe in 2019 when there were no storms forecast. I also had one of my clients tell me they had a near miss: “Everything went loud and white; I was blinded for several minutes. When I came back to my senses I realised I could smell my singed eyebrows!”

Even if it’s a remote risk, take the risk seriously. Plan your day around it, the way you would for avalanches, monitor conditions and be prepared to cut your day short.