Meridional weather patterns and rapid temperature variations

Within the space of a few days, we've jumped from basking in hot sunshine at the end of May, to shivering in a chilly northerly gale by the first weekend of June.

Such is the variability of our great British weather. As always, it all comes back to wind direction and air sources. We've seen Scandinavian air masses a lot recently, but in late May, this air originated from southern Europe and even parts of central Russia. When high pressure, dry air and clear skies were abundant, this brought stable air and warm, sunny days.

Over the past few days we've seen an area of low pressure form over Scandinavia, and pivot across Britain from the North Sea, dragging air out of Arctic regions towards our shores. Colder air at higher levels in the atmosphere has been the trigger for instability and showers.

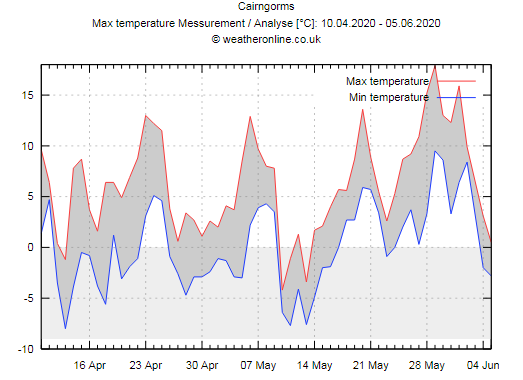

Temperatures have fallen markedly - from hitting the upper 20s in Highland glens last week, to single digit maxima in recent days, and sub-zero temperatures down to Munro levels on the mountains, plus a dusting of snow lying at least temporarily on the tops.

Cairngorms, 5th June 2020. Photo: Peter Jolly.

It's not the first time this spring we've seen temperatures jump around quickly. The graph of Cairngorm summit temperatures over the past 6 weeks (below) shows a very spiky profile of rise and fall, with periodic northerly incursions bringing notably chilly air. We had a similar pattern in early May for a few days when the mountains also went sub-zero.

Although it's considered rather 'unseasonal', it's not that uncommon for our mountains to see such wintry episodes well into spring. Early June is pushing the limits a bit, but it's still perfectly achievable given the right weather setup.

One past very notable June cold snap back in 1975 infamously brought snow to the Peak District and stopped a cricket match in Buxton! The synoptic weather pattern of that period was actually quite similar to now, but with slightly colder air drawn in directly from the Arctic.

When the upper atmospheric patterns are more 'meridional', that is, air flowing north-south rather than the more common 'zonal' westerlies, it means we can easily get these rapid fluctuations in temperatures. Spring 2020 has seen the jet stream take a more meandering pattern than average around the northern hemisphere, locking in place these more 'unusual' weather regimes for periods. West and northern Europe has seen high pressure commonly in charge, hence the sunshine and dry weather which has prevailed.

These patterns are very much part of the natural variability of weather, but there's a strong suggestion at least that such occurrences become more common with a warming Arctic region. Weaker temperature gradients between the pole and the mid-latitudes have a knock-on effect to the large scale weather patterns.