A squeeze of air over the hills

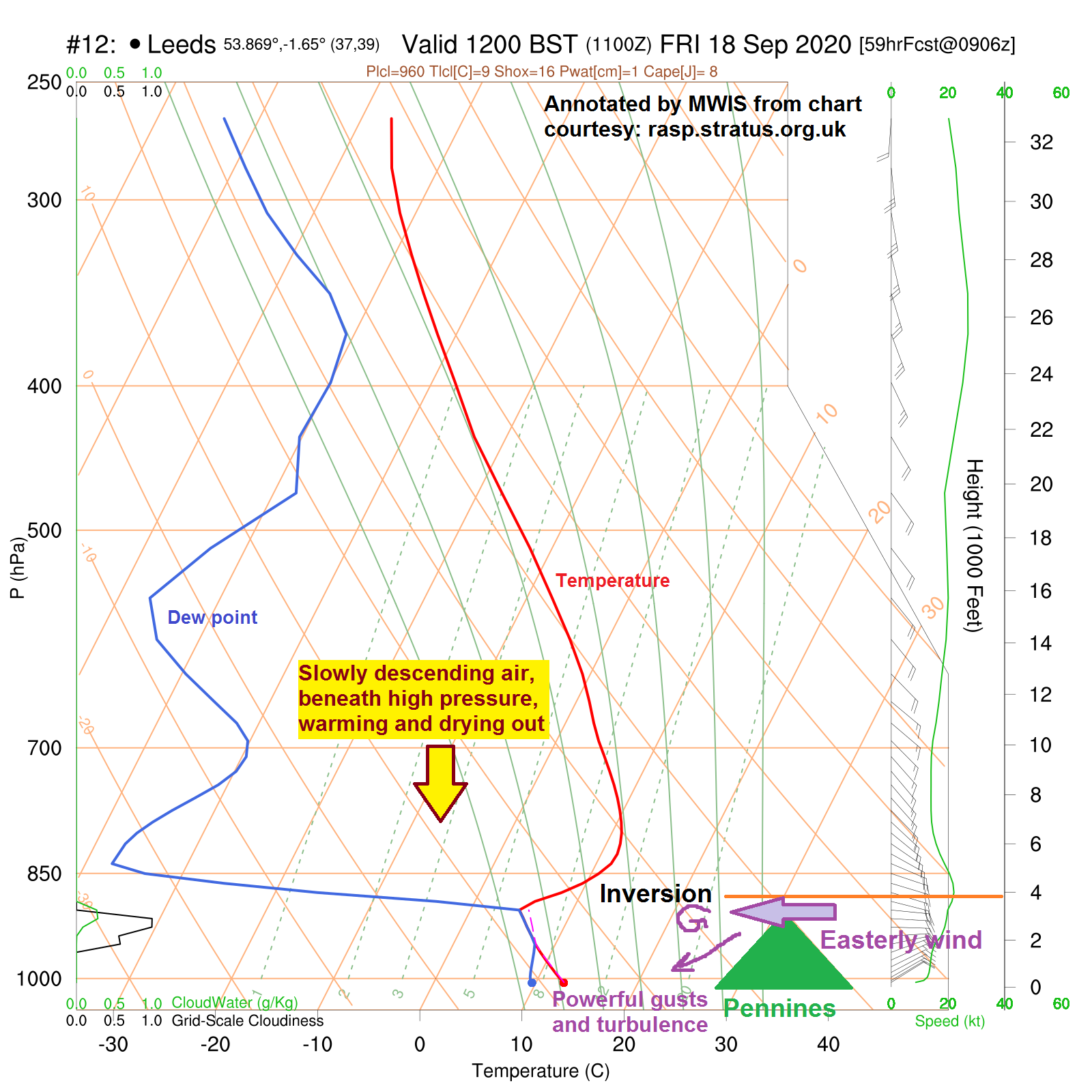

Our old friend the inversion will play another role in our mountain weather later this week.

We've seen examples of low-level fog, and how wave clouds can form beneath inversions. On this occasion, we're looking at the role an inversion can have on wind enhancement, which will be occurring in the days ahead.

High pressure is becoming established around northern Britain, turning the wind flow into an easterly across England and Wales. Fairly complex centrifugal forces mean that wind tends to be stronger around the flanks of highs than would be seen for the same spread of isobars around lows, so we're already prepared to up the ante on wind speeds in this kind of pattern.

Add to this the familiar formation of an inversion as air sinks slowly within the high pressure area, allowing a slight warming of the air aloft, but trapping a layer of cooler air nearer to the surface.

Subtle temperature contrasts from north to south across Britain in the current pattern also contribute to a wind enhancement, with a reversal of a common meteorological theme, whereby warmer air exists with a zone of low pressure lying to our south, but that gets rather technical.

Easier to envisage is the presence of an inversion, acting as a lid on the lower atmosphere, meaning air cannot easily rise. This is what we call a 'stable' situation. There's no frothing thundery shower clouds in this set up!

The exact height of the inversion, which can vary day to day or geographically, is crucial in relation to the height of our hills. When it lies just above many higher tops, say in the 3500-4500ft layer, it means there is just enough space for the prevailing airflow to pass across the hills, but it is rather squeezed. The result is much like a stream which is forced between two narrowly spaced rocks - it speeds up the flow and breaks into turbulence. The same is true in the atmosphere - causing sudden bursts of wind to surge downslope from the hills, into passes and to lower slopes. The most powerful gusts occur in areas which would be considered to be in the lee - i.e. to the west of major ridges.

The Pennines form an excellent barrier to the easterly wind, meaning the air cannot just divert elsewhere. The result is the UK's only 'named' wind - the 'Helm Wind of Cross Fell'. Helm is a little village in the Vale of Eden, and is more or less in the firing line for sudden easterly gusts which literally come 'roaring' down the valley at gale force. You can hear it coming!

The 'Helm Bar' is a familiar accompaniment - a smooth elongate banner cloud caused by the turbulent air currents rising and falling, and can stay in position for several hours whilst the wind ripples through it. If you see one this weekend, send us a pic via the MWIS social feeds!

Similar concepts occur over the Highlands under stable southeasterlies, when areas just north of Aonach Mor and the Cairngorms receive locally ferocious gusts.

On days when the inversion is lower, and usually a less windy situation overall, the strongest winds can be found lower down around the hills and valleys, whilst up on top is relatively benign.

As always, it's all just the fascinating physics of the atmosphere in motion. Remember that if you're having problems with the wind this weekend...!